Greetings once again from Brighton Beach!

In this Atlantic coastal neighborhood we enjoy the calmly sparkling speaking seriousness of beach sun—here the sun has character, you might say—which only a short distance inland turns to severity, or turns indifferent, or, as enough vapors intervene, drifts past consideration. Sit by a west facing window down here with a bit of sky in view, shut your eyes, you’re transported to the blue waves’ edge, the day star’s all-reflecting splendor falling from the right on your glowing head. How pleasant to sit among cushions, indoors, with cats, and take this particular spin. But even as I sat down to write about it, I was thinking of this as an old—an older—person’s pleasure; I’d remembered how in my parents’ final apartment, my father who was almost blind by then had one of their big Mission oak armchairs, maybe the one I have now, in a spot of strong daily sunlight—Atlantic coastal sun too, by vague coincidence. Aging is a gradual approach that’s not entirely a return to basics: there’s a definite angle that covers new ground, and an endpoint in sand not flesh. To sunbathe at the seashore is a human joy that connects us with birth, our naked selves exposed to naked light. To lie on the beach while sitting indoors in a sweater, with a couple of cats and maybe a heating pad for the back, is an innovation that comes to the old mind.

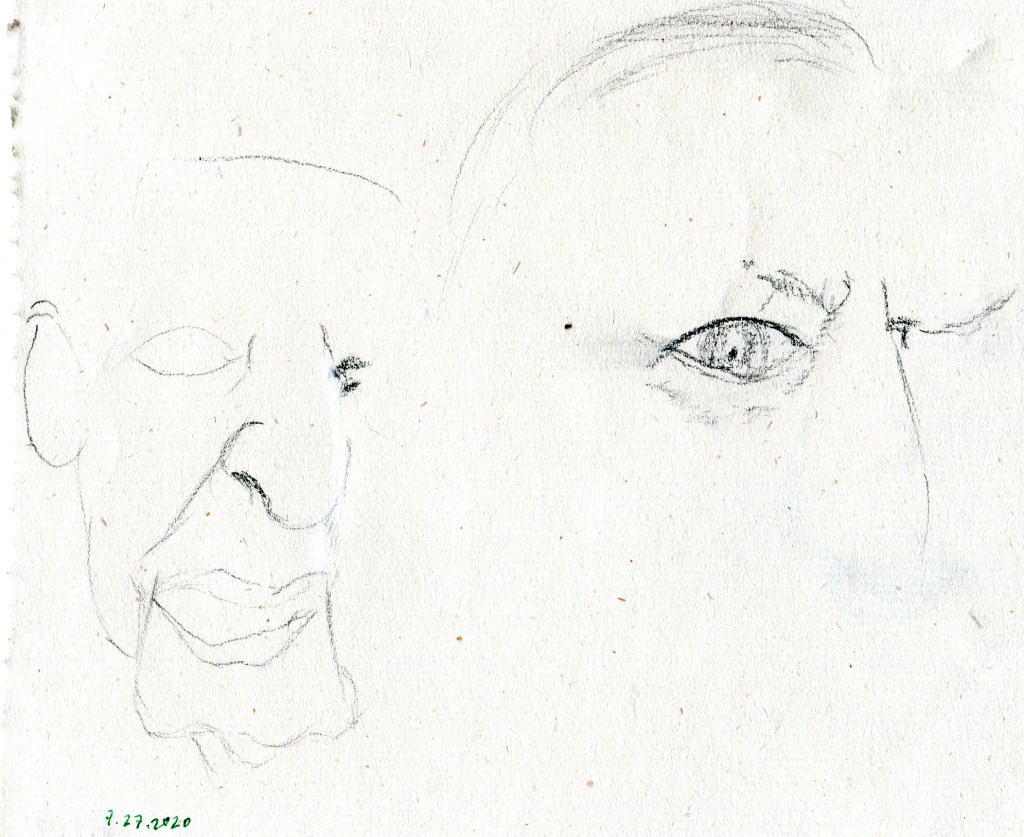

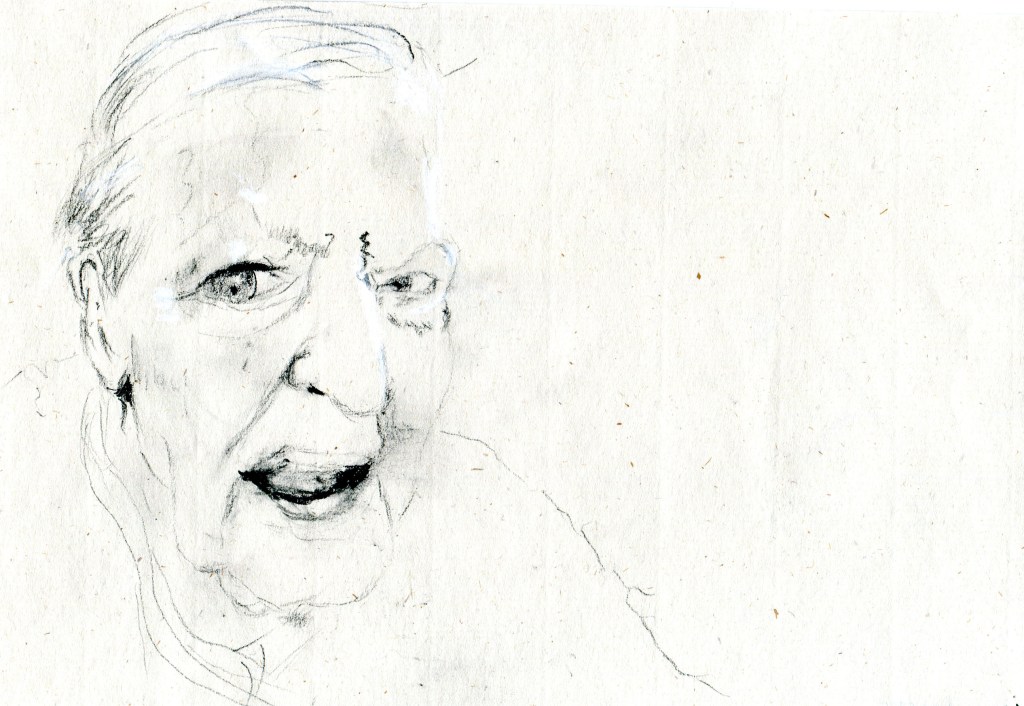

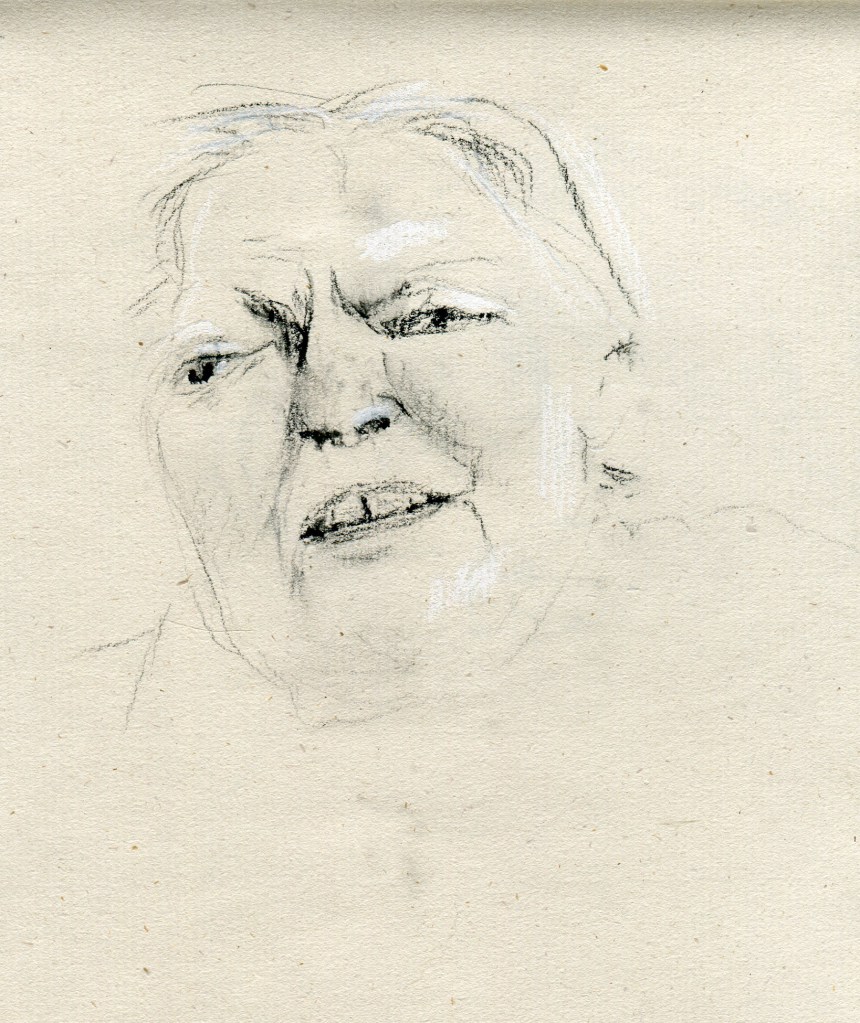

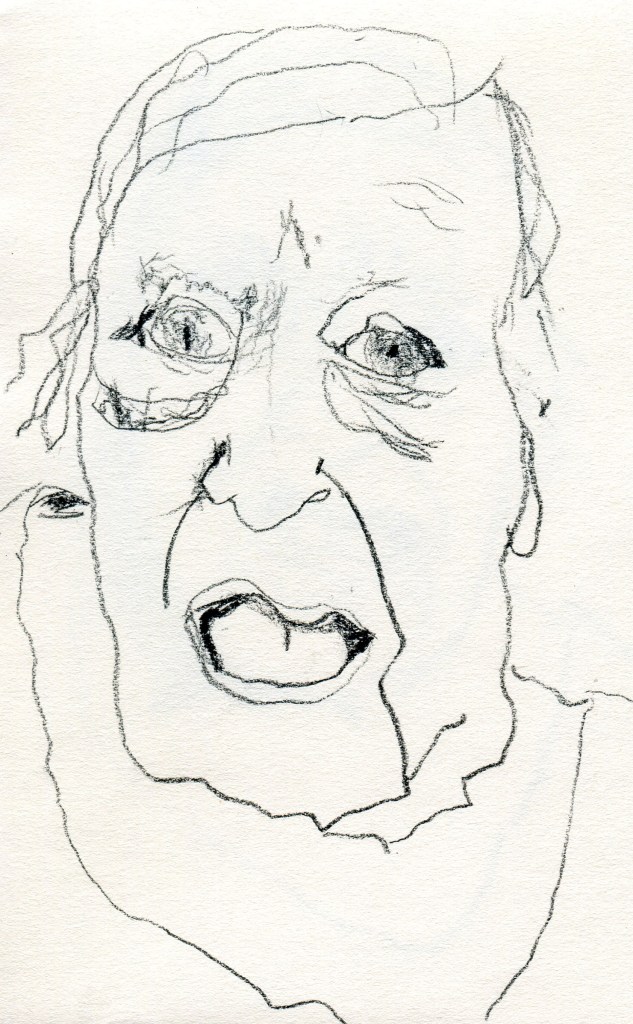

My mother, who survived my father, promised me of her own accord and practically out of the blue each time—for it was more than once she made this promise to me—that she wouldn’t live past ninety. Nevertheless she died at ninety-one. Her last years of widowhood she spent bedridden or sometimes in a wheelchair at the last place she’d have wanted, in a nursing home. Fortunately a very good one; and because her much younger roommate shunned the outside world my mother always got the window and the sun—standoffish inland sun that side of Boston. Starting with the COVID lockdown my sister and I were able to talk to her from our separate apartments in Brooklyn on weekly Skype calls; we’d take screen grabs with noisy clicks that must have bothered her. Maybe I was goading her to say so. She no longer talked, though; so mostly we’d chatter away with the roommate lying out of frame. I sketched my mother off and on from the screen grabs, including a few times with my left hand after she’d died: on a trip up there to gather her things from the nursing home I’d broken my drawing wrist trying to learn pickleball.

Borderline osteoporosis notwithstanding, my own decrepitude is still a long way off, I hope. What I notice in the run-up is discomforts, often sharp and nauseating, produced and/or provoked by my environment—the present environment—the Present. A time of chemical body sprays and vape steam clouds: the smells torture me. So does most popular music. Autotune in my ears for any length of time gives me anxiety symptoms that range from severe to (in the case of a couple of Rihanna songs that still get play) unbearable. Which, I’ve realized, is what happens. Always, at all times, of low quality, the popular culture necessarily wants youthful attention, youthful, fecund, so called-aspirational allegiance, all the young eyes on it; and it wants this to the deliberate, calculated, across-the-board exclusion of “the old,” who recognize its defects. Popular music is not being made for me: proof, it makes me want to throw up. There were people who said the same thing about the Beatles’ music, and Elvis Pressley’s music, people who objected on physical grounds, perceiving their own health attacked; people in the process of being left behind by the larger environment outside their own homes. So too I find myself increasingly reluctant to venture into settings where I can predict I’ll suffer—settings like the beach, sadly.

Also professional baseball and tennis in person; sad again because I love them both and I write about tennis. Like an invasive vine, hugely amplified popular music has filled every sweet pocket of murmuring quiet the two sports used to offer: always those built-in breaks for silent meditation were so attractive to me. To us, the old. That dreamy scene we knew has been erased. What’s there now is very loud, and those like me who can’t take it are driven away.

My guess is that a lot of the empty seats I see at the very many tennis matches I stream on-line (muting liberally) represent loyal, well-off old fans who’ve decided not to buy or use any more tickets for this very reason. They figure the people running the tournaments must be desperate to replace them with younger fans, in whose pursuit the sport they loved has been disfigured almost past recognition by digital uproar. I try to picture what my parents would have made of the US Open now. I was there with them several times up until about 2005, they acquired a lot of merchandise. Many good memories I have of those times. As I recall, music they both thought terrible played in a few spots on the grounds; then as in the 2020s, iffy live singers opened the night sessions. But the DJs and the shrill hideous bleating, blatting, buzz-sawing, head-splitting racket that’s outside and on the courts now, whooshing and thumping, no way would I be able to get my parents out of there fast enough—one of them would have a fall or some major incontinence first, it would be a nightmare scene. Then I realize: my parents were on the old side for the place twenty years ago. What they could experience had limits, there was only so much unpleasant change their lives, though very long, could span. These present trials are for my cohort.

It all makes me think about the women who were hitting old age when everyone else started smoking constantly. Say they’d passed on being Flappers in their youth, and now it’s 1949. Everyone is doing it, men, women, young folks, lighting up, inhaling, releasing smoke clouds and ash, grinding ends into ashtrays, leaving burn marks, occasionally starting accidental fires: strange new behavior, the latest in a long line; if you’re around long enough you’ll see crazes come and go, it’s true. Having weathered so much since their birth as female in the 19th century, maybe they could have handled unfettered Big Tobacco. If not for the smell, that is. Suddenly, their entire olfactory world of myriad recognitions and innumerable comforts and delights—leveled. The distinctive atmospheres of different neighbors’ homes—homogenized in gray. Socializing, which once supplied vital contact and nourishment, becomes the occasion for appetite loss, eye inflammation, and soon-to-be-bronchial complaints. Their pets recoil from the cigarette funk on the clothes they wear home; they tire themselves out scrubbing, scrubbing, their hands and scalps develop painful red raw patches. The smart ones, maybe, will stop going out. The most unfortunate will fold along “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em” lines and take up the habit which will consume and poison the life that remains to them, turning it into a choke-chain of necessary pleasures—Present pleasures, with no end allowed.

Of course my mother would have envied these women their predicament, these old women who kept on smoking as she finally didn’t and always regretted it, saying so often and plaintively—how she missed smoking! I who never miss it feel sadder for unfortunate old women who in my mind lived innocently, amid the smells of pies and starch and wood and rain, who’d giggled maybe three times over herbal liqueurs; until they lived too long and overlapped a time too perilous for what they brought to it. They died helpless, addicted, gripped by cravings, deprived of peace, denied the good quiet deaths they might have had coming to them otherwise.

The way I fear and/or expect I might die feeling maddened by an aide’s so-called fragrance.